Anger, and the Roar of the Wild Writer

/Ok, let’s start with the sensible guidelines about putting anger effectively on to the page. And then we’ll see why wild writing means throwing those rules out, at least partially.

Read MoreBlog

We unpeel those layers that have attached themselves over time, by finding word portals back to a freshness of thought and expression.

The ‘Aha!’ moment of the reader is also the instant the writer is liberated. To get there, write as if experiencing something for the first time.

Use humour on the page – especially in situations that aren’t at all funny…

Move into close detail – of both inner and outer experience…

Once, in millennium not long before this one, I lived in a Forest…

Martha’s story began, in the way of many, as a glimmer in the back of my mind…

Ok, let’s start with the sensible guidelines about putting anger effectively on to the page. And then we’ll see why wild writing means throwing those rules out, at least partially.

Read More

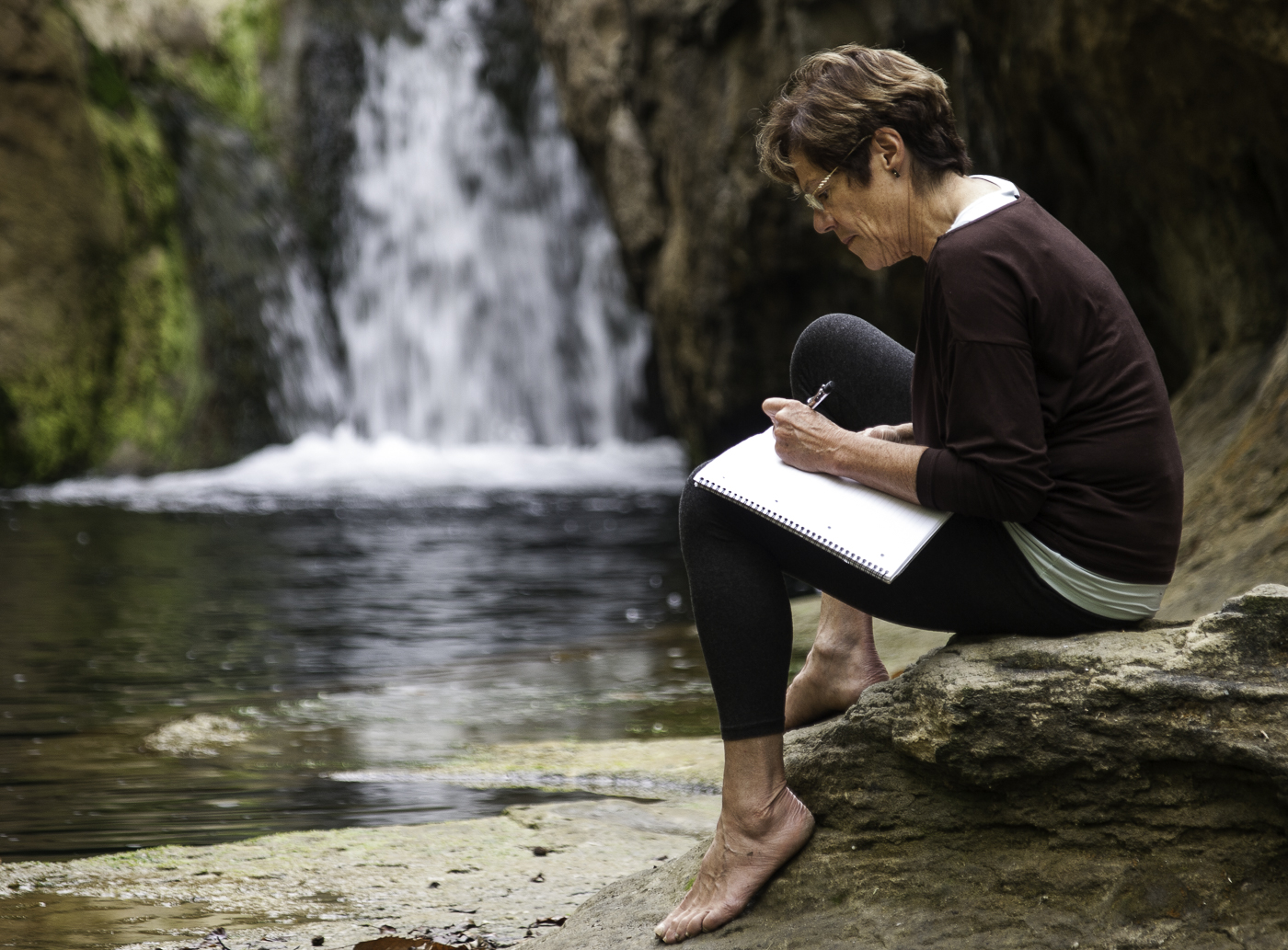

The Wild Words Retreat. Photographed by Peter Reid.

Reading or listening to stories imbued with emotion stimulates much more of the brain than reading an emotionless account would do. The empathy areas light up, and oxytocin, a chemical related to feelings of love and trust, is released.

When our words are imbued with emotion, for both the storyteller, and the listener or reader, it’s like having the wild animal very close, breathing down our neck.

These wild words hook the reader. The power and the passion within them sweeps us along, all the way to the end of the story. There is nothing tame about these words, nothing predictable. They live in extremis. One moment the receiver is roused to laughter and joy, the next they are devastated by tragedy. Hooked by emotion, they journey with the narrator/lead character. It’s quite a trip.

Rachel Shirley gives a relevant example of how to work with emotion on the page. She explains that you could write,

She waited by the door. She felt so frightened, she thought she would begin to panic.

However, it would be stronger to write,

She waited by the door. Her heartbeat thrummed against her ribcage, her mouth tasted like iron and her breaths hitched in her throat.

Although wild words are infused with emotion, as you’ll have noticed in the above example, the emotion is often not named on the page.

Instead the experience of feeling emotion in the body, which is actually the experience of the intensifying of bodily sensations, is described. As these experiences are common to all of us, we know exactly what emotion is being experienced, even if it’s not named. Indeed, it’s more impactful for not being named.

Below is a wonderful (if stomach turning) example of how to work with emotion on the page, from Ian Fleming’s ‘Casino Royal’. Le Chiffre is torturing Bond. Notice how the emotions are never named, but there is attention to the detail of bodily sensations.

Bond's whole body arched in an involuntary spasm. His face contracted in a soundless scream and his lips drew right away from his teeth. At the same time his head flew back with a jerk showing the taut sinews of his neck. For an instant, muscles stood out in knots all over his body and his toes and fingers clenched until they were quite white. Then his body sagged and perspiration started to bead all over his body. He uttered a deep groan.

My first thought was that it should be a Young Adult self-help book, as I’d already written 8 self-help books for children, but my agent couldn’t get a publisher on board with it. She suggested I might write it as a novel instead.

I finished the first version of my novel, Drift, more than 10 years ago, and several publishers expressed interest in it, but they all eventually decided that the story was ‘too quiet for the market.’ They said it needed a ‘strong hook,’ that is to say, to be out-of-the-ordinary in some striking way.

But my reason for writing it in the way I had was because I wanted to help other survivors of sibling suicide to feel less alone in that already extraordinary grief. The whole point of my book was that it should feel real; it should feel like any young person’s life, suddenly disrupted by something that could happen to anyone.

I knew I had written a good book and I wasn’t willing to compromise it by sexing it up, so I shelved it and tried to forget about it, but it wouldn’t go away.

So when I got a new agent a few years later, I sent it to her. She liked it, but told me she found the most dramatic passages weirdly unmoving.

I rewrote the whole novel, this time fully inhabiting the main character, and it was the hardest rewrite I’d ever done, but the experience broadened my reach as a writer. Where previously I had invariably used humour in stories about difficult subjects such as bullying, now I found I could lay down that armour if I wanted to. It felt brave.

My agent sent the revised version out to publishers. They still found it ‘too quiet’ so I brought Drift out myself on September 10th 2015, to mark World Suicide Prevention Day. I later realised that my choice of publication date was almost exactly 40 years to the day after my sister’s death.

Drift has received wonderful reviews so far and has just been included in the list of books recommended by Cruse, the UK’s largest charity for the support of bereaved children, young people and adults. When I saw that on their website, I felt I had done what I set out to do.

http://jennyalexander.co.uk/young-adult

http://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/191030008X?keywords=jenny%20alexander&qid=1453380135&ref_=sr_1_6&sr=8-6

Wild Words - Nature-inspired creative writing for wild writers and storytellers with Bridget Holding.

Wild Words is a call to express the wild in you. For anyone who has a yearning to express themselves. In conversation, spoken word, storytelling, songwriting, writing (poetry and prose, fiction and non-fiction).

Website by a monk

Winter Solstice Competition Runner-up: Hannah Ray, with You Were Born in a Pandemic